Where Barbecue Began

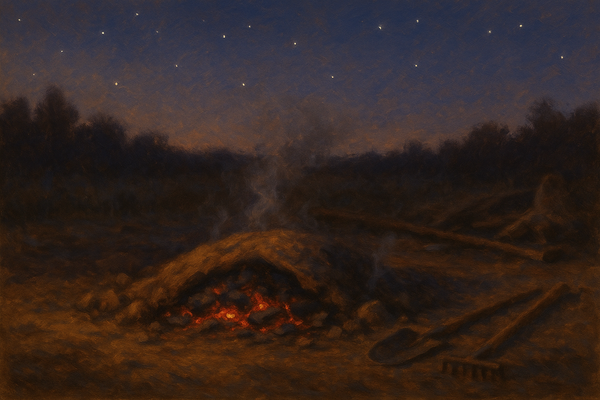

Before there were gas grills, sauce debates, or backyard competitions, there was a hole in the ground and time.

Barbecue, in its oldest American form, wasn’t about equipment or even recipes. It was about patience, wood, and the kind of slow heat that changes both food and people.

The earliest written records of “barbacoa” come from the Caribbean, where the Taíno people cooked meat over green wood racks suspended above smoke-filled pits. When Spanish colonists saw it, they took notes — and eventually took credit.

But the method spread north, adapting to local landscapes and ingredients. In the American South, it became a way to cook whole animals low and slow, sealed in earth to keep in moisture and smoke.

Fire in the ground wasn’t just cooking. It was community.

The Fire Beneath the Surface

Here’s the quiet genius of it: cooking underground is less about flame and more about retained heat.

When you dig a pit, line it with stones, and build a hardwood fire until it burns down to coals, you’re creating a primitive oven — one that radiates evenly from every side.

The soil acts like insulation. The coals at the base act like the heartbeat. You cover the food, seal in the heat, and walk away.

It’s as close to cooking with time itself as you can get.

Scientifically, pit barbecue is an exercise in thermal inertia. The heat transfer happens through conduction (from the coals), convection (from trapped air), and a little radiation (from the glowing embers). It’s slow, steady, and self-regulating — which is exactly why it works.

The result isn’t just tenderness. It’s depth.

You get flavor that doesn’t shout; it hums.

The Ritual of Digging

Digging a pit sounds primitive until you do it. Then you realize it’s meditation disguised as work.

You measure by instinct, not inches. Three feet deep, maybe four, depending on what you’re cooking.

Hard clay holds heat better than sand. If the soil’s damp, line it with river stones or bricks to protect the base from steam.

Once the hole is ready, you start your fire with hardwood — oak, hickory, mesquite if you can find it. It burns hot and clean.

When the flames die down to glowing coals, you lower in the meat, wrapped in soaked burlap, banana leaves, or foil, depending on how close to the source you want to get.

Then comes the part most modern cooks can’t stand: you bury it and walk away.

You don’t check. You don’t peek. You trust heat to do what you can’t.

What Happens Underground

Inside that sealed earth, something ancient happens.

As the temperature stabilizes between 200°F and 250°F, connective tissue melts into gelatin. Collagen unwinds. Fat renders slowly, dripping down to kiss the coals and return as smoke.

That smoke rises, circles, and settles again — not the acrid sting of direct fire, but a whispering perfume.

Every minute compounds into something deeper, something that tastes like patience and weather and soil.

In scientific terms, you’re watching both Maillard reactions and fat oxidation at play, working in harmony.

The Maillard reaction builds savory, roasted notes. Oxidation softens fat into sweetness. Together, they turn raw flesh into something both elemental and refined.

The earth keeps the temperature low enough to avoid burning but high enough to build character.

When you dig it up hours later, it’s less about unveiling food and more about uncovering history.

How to Do It Yourself (Responsibly)

You can still do this today — no smokehouse, no gadgets, just the basics.

Here’s a simple, respectful way to try pit barbecue yourself.

1. Find the right spot

Pick a safe, clear patch of ground away from roots, trees, and anything flammable.

If you’re on private land, you’re fine. If not, check local regulations. A permit might save you a conversation later.

2. Dig the pit

Aim for about three feet deep and three to four feet wide.

If you’re cooking a whole pig, you’ll need bigger. For a shoulder or ribs, this is plenty.

Line the bottom with flat stones or bricks to hold and radiate heat evenly.

3. Build your fire

Use hardwood — oak, hickory, or fruit wood. Stack it tightly, light it, and let it burn down for two or three hours until you have a deep bed of glowing coals.

This is where your heat will come from, so give it time to mature.

4. Prepare the meat

Season generously. Salt, pepper, and smoke are the original trinity.

Wrap it tightly in soaked burlap, banana leaves, or foil. Burlap and leaves breathe and add flavor; foil traps moisture but keeps the flavor cleaner. Your call.

5. Lower and seal

Lower the wrapped meat into the pit, about a foot above the coals.

Cover it with a layer of damp burlap, then a sheet of tin or an old grill grate.

Pile on a few inches of soil or sand to trap the heat.

At this point, your job is patience.

6. Let time do its work

A pork shoulder will take 8 to 10 hours underground.

A whole pig, closer to 18. The goal is an even, gentle temperature. If you open the pit, you lose the magic.

Trust the ground to do what your oven can’t.

7. The unearthing

When the time’s up, brush away the soil, lift the lid, and unwrap slowly.

The smell hits first — deep, smoky, and sweet in the way only fat and wood can make.

The meat should fall apart with a spoon, its juices thick and caramelized.

That’s your reward for staying out of the way.

The Social Side of Smoke

Barbecue started as community food.

Whole animals, shared effort, long waiting. The fire was the centerpiece because it demanded attention — not from one person, but from everyone.

Even now, digging a pit brings people together in a way modern cooking rarely does. You can’t scroll through it. You have to show up, wait, and share.

That’s the real legacy of barbecue. Not the sauce, not the trophies, not the arguments over smoke rings.

It’s the act of cooking something for hours so everyone can eat at the same time.

That’s history you can still taste.

Conclusion: The Fire Still Burns

Digging a pit to cook in the ground feels radical now, but it’s one of the oldest ways of feeding people we know.

It’s slow, smoky, and stubbornly human — a conversation between fire, earth, and time.

The science explains the heat transfer. The heart explains the hunger.

And when you lift that first piece from the pit, tender and perfumed with smoke, you taste something older than recipes.

Because every flame tells a story.

And the best ones still start underground.